News / March 27, 2017

To Protect Our Water Resources, Plant a Tree

Trees are the unsung heroes of urban life. It’s hard to overstate their benefits: They filter pollution out of the air, lower our energy bills, undercut the misery of summer heat, raise property values, reduce mental stress and generally enrich our lives in a variety of ways that are both surprising and well-documented.

But trees provide another important benefit that is often overlooked: They play a hugely important role in protecting our water quality.

In Minneapolis, a single tree intercepts an average 1,685 gallons of rainwater each year, according to a 2005 study. If not for the tree, all of that water would fall to the ground, and much of it would become runoff. Instead, the tree captures, stores and uses it.

Multiply this effect by the city’s estimated 200,000 street trees, 400,000 park trees and hundreds of thousands of privately owned trees, and you’ll get a sense of how much water is intercepted by the urban tree canopy — and that’s just in Minneapolis.

Trees keep billions of gallons of stormwater out of our storm drains each year in the Twin Cities metropolitan area. Instead of gushing through our stormsewers, carrying pollutants from our streets and lands into nearby waterbodies, that stormwater becomes a part of the natural water cycle, soaked up by trees and returned to the atmosphere.

The more trees we add to our landscape, the less pollution will flow to our waters. And with the threat of climate change and the invasive pests like emerald ash borer looming, planting new trees is more important now than ever.

How trees protect our water quality

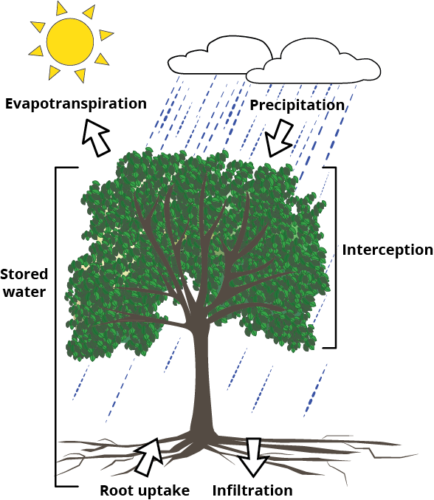

Trees are excellent at managing stormwater. In essence, they act like mini-reservoirs, capturing and storing rainfall and melting snow. This helps reduce the volume of stormwater runoff that enters our stormsewers.

Here’s a more detailed explanation of how trees mitigate stormwater runoff:

Interception — Rain falls on the tree’s leaves, branches and trunk. Some of it is absorbed by the tree, and some of it evaporates back into the atmosphere. The rest falls through to the ground, but at a much slower rate than it would otherwise. This helps reduce “peak flows” during rain events and also helps prevent soil erosion.

Infiltration — Water that falls through the tree canopy soaks into the ground and gets absorbed by the tree’s roots. By soaking up water from the ground, trees add capacity for the soil to store even more stormwater. As they grow, the roots also help break up compacted soil, which allows water to more easily move downward into the groundwater table.

Transpiration — The tree draws water out of the ground to use as fuel for photosynthesis. The water is later released back into the atmosphere as water vapor. This normal part of the water cycle also helps to cool the air and reduce high temperatures in the summer.

Planting trees in a changing climate

Planting a tree is a relatively straightforward process, and there are many guides available online. If you want to go in-depth, the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources offers detailed instructions on selecting, planting and maintaining trees. Or, if you’re feeling confident and want to skip ahead a bit, you can check out the Tree Trust’s handy how-to video, which demonstrates the increasingly popular “box cut” method of planting containerized trees.

But before you head to your local nursery, you may want to spend some time thinking about what you want from your trees. Some tree species are better than others at things like managing stormwater runoff, providing shade, mitigating pollution and providing habitat for wildlife.

For example, a Swamp White Oak is said to support 300 times the amount of wildlife species as a Gingko. Bur Oaks, meanwhile, are known to absorb large amounts of nitrogen pollution. Likewise, certain tree species are known to be especially good at intercepting and storing large amounts of stormwater. Common local examples include American Elms, Basswoods and Silver Maples. (A less fortunate example is Green Ash trees, which are now threatened by Emerald Ash Borer and being systematically removed in some places.)

Naturally, mature trees with large canopies are better at mitigating stormwater runoff and will provide more shade. If you’re planting a new tree, it will be quite some time before you’re able to reap the full benefits — which is all the more reason to plant sooner rather than later.

The looming threat of climate change raises a new set of considerations when choosing a tree. Research has indicated that a warming climate is likely to dramatically transform Minnesota’s forests, and urban forests are no different. You should consider selecting tree species that are likely to be resilient as the state’s climate begins to warm. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency offers a helpful chart for doing so. Here at the MWMO, we’ve planted a number of species such as Hickory that are traditionally more acclimated to southern climates, but which are likely to thrive in Minnesota in the future.

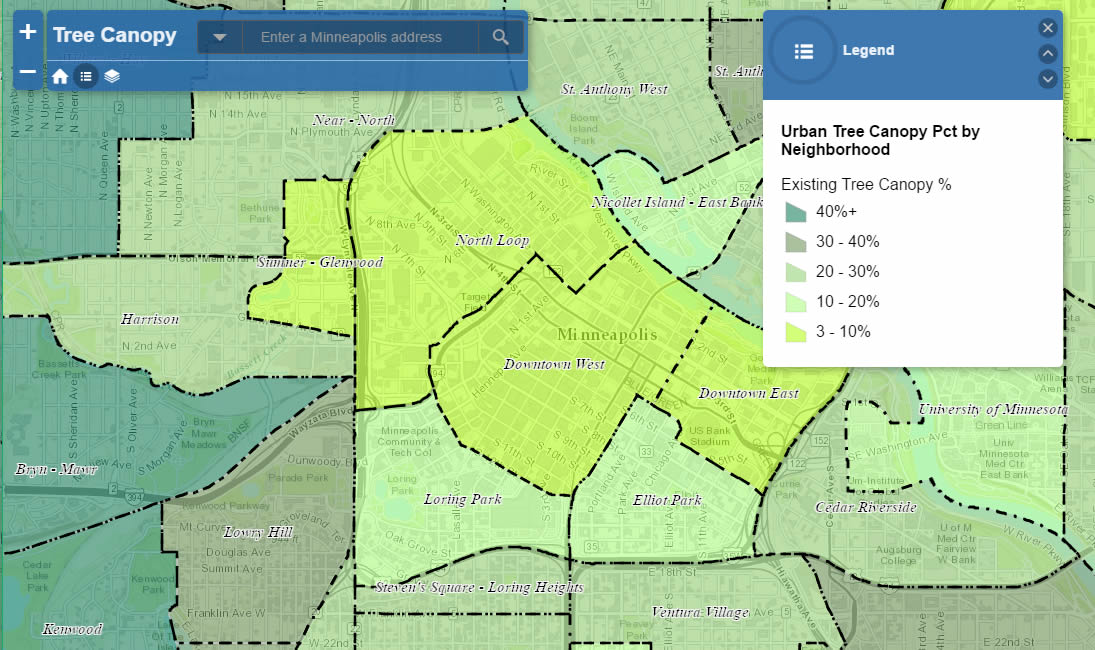

In case you’re wondering, there is plenty of room to expand the urban tree canopy — even in our most developed areas. A 2011 study found that approximately 31.5 percent of Minneapolis is covered by tree canopy. The number might seem impressive at first glance — and to be fair, it does put the city slightly ahead of the national average. But the same study found that Minneapolis could support up to an additional 37.5 percent tree cover, more than doubling the city’s current tree canopy.

Imagine a future where the state’s largest, densest, most populous city is more than two-thirds covered by tree canopy. And then imagine this success being repeated in communities around the state. It’s possible, at least in theory.

Cleaner air, lower temperatures, healthier people

This post is about trees’ ability to mitigate stormwater runoff, but I would be remiss if I didn’t at least mention their other environmental benefits. In urban environments, trees simultaneously purify the air and lower the air temperature. These two processes feed off of each other in a virtuous cycle that literally saves human lives.

Trees filter pollution out of the air by trapping particulate matter like dust, ash, smoke on the surface of their leaves, and by absorbing gaseous pollutants like ozone and nitrogen oxides. This reduces the amount of harmful material we inhale into our lungs. This effect is good for indoors as well as outdoors; one study found that a row of street trees can reduce the presence of particulate matter inside houses along the street by 50 percent.

Meanwhile, trees also lower temperatures in cities. They do this in two ways: by providing shade and through evapotranspiration. The first way is obvious: stand under a tree on a hot summer day, and its value as a provider of shade will become immediately apparent. But trees also evaporate and transpire water into the atmosphere (similar to the way humans sweat). That additional moisture cools the surrounding air temperature.

Together through these processes, trees reduce something called the urban heat island effect, whereby large cities, with their abundance of hard, heat-trapping surfaces, grow hotter than rural areas. Studies have shown that trees can reduce peak summer temperatures in cities by 2 degrees to 9 degrees Fahrenheit. In addition to making summer heat waves less miserable (and for some, more survivable) these lower temperatures reduce the need for air conditioning, which saves energy costs and cuts down on pollution from electric power plants.

The Nature Conservancy documented these effects well in a 2016 report called Planting Healthy Air that examined the relationship between tree cover and air quality in major urban areas. (The report’s web page features a fun, interactive story map to boot.)

Special thanks to Professor Gary R. Johnson of the University of Minnesota’s Department of Forest Resources for his assistance with this article.

Bonus: Some Really Cool Maps

Minneapolis Tree Canopy Map

U.S. Forest Service Tree Canopy Map

MIT Treepedia