News / December 14, 2018

A Drone’s Eye View of the Watershed

Understanding landscapes is fundamental to our work at the MWMO. Having a clear picture of the land — its uses, its contours, its vegetation — helps us understand how water interacts with it. That knowledge is critical for helping reduce the flow of pollutants from the landscape into waterbodies.

We recently acquired a new tool that allows us to see landscapes in an entirely new way: a drone. Also known as unmanned aerial vehicles, drones are aircraft piloted remotely by human operators on the ground. Until recently, drones were large, expensive, and operated mostly by militaries. Within the last five years, however, a new generation of small, affordable, user-friendly drones has come on the market, offering professionals and consumers easy access to aerial photography, 3D mapping and a variety of other applications.

At some point last year, I pitched the idea of the MWMO buying a drone as a way to better document our construction projects. Many of our large capital projects involve transforming blighted urban landscapes into green infrastructure. Such transformations can be hard to capture from the ground. You can stand next to a rain garden and know that it used to be a parking lot, but seeing it from the air gives you a better sense of context — of how that particular stormwater feature serves a purpose in relation to the broader landscape.

Our staff also thought of a number of other potential uses for a drone. The planning and projects team thought we could use a drone to survey potential project sites that are difficult to access from the ground. Our monitoring team thought a drone might also be a helpful tool for their lake and wetland monitoring tasks. And outreach staff thought drone footage might help residents understand stormwater pollution better.

After assessing our needs and researching the various products on the market, we selected the DJI Mavic Air — a small but robust drone with excellent portability, a good camera and an agreeable price tag. Before we made the purchase, the next step was for me to obtain a remote pilot certificate from the Federal Aviation Administration.

A remote pilot certificate is required for any kind of professional drone work. Fortunately, earning a certificate is easier than it sounds. Essentially, it requires passing a knowledge test that covers basic airmanship, including airspace classifications, weather sources and effects, radio communications, and various operating rules. It’s a fair amount of information to absorb, but nothing that can’t be mastered over the course of a few weeks of self-study. After I successfully passed my test in June, we bought the drone, filed all the necessary paperwork and set about capturing our work in a new and exciting way.

The Challenges of Flying a Drone in an Urban Environment

Flying a drone in an urban area is a tricky business, as pilots must pay heed to a slew of overlapping federal and local regulations. Most of these rules are designed to protect human lives and property, so ignoring them is not an option.

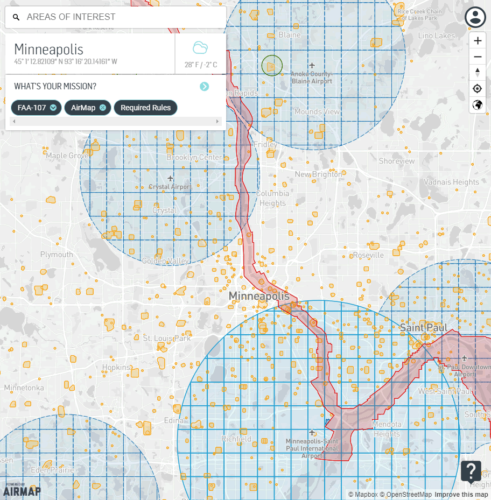

One of the biggest issues we face is the prevalence of controlled airspace in our watershed. Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport, Crystal Airport, and Anoka County-Blaine Airport all have airspace that overlaps portions of our area. Operating anywhere near these busy airports requires authorization from air traffic control — a precautionary step designed to help avoid any possibility of a mid-air collision. There are also heliports in and around downtown Minneapolis. These generate unpredictable, low-flying helicopter traffic that must also be carefully avoided. During professional sports games, a large portion of Minneapolis is often designed off-limits to drone flights as well.

Drone pilots must also be mindful of restrictions on the ground. The Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board (MPRB) and the U.S. National Park Service (NPS) both prohibit drone use in their respective parks. These restrictions help protect visitors’ experiences at the parks, as well as discourage careless drone operators from harassing wildlife. They do create challenges for the MWMO, however, as many of our projects are on MPRB land and/or lie within the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area. (Fortunately, after reaching out to NPS, we were able to get permission to fly in most of our areas of interest along the river. We do avoid flying over MPRB land, however.)

Then, of course, there are the federal regulations. For starters, drones generally can’t fly higher than 400 feet above ground level (and no higher than 500 feet below clouds). They also can’t fly over people (unless they are willing participants). Drone operators must keep their drones within a visual line of sight at all times, and cannot fly in less than three miles’ visibility. A quick glance at the FAA’s summary of rules for commercial drone operators (PDF) should give you a sense of the complexity that goes into planning each and every drone flight.

Fortunately, I’ve discovered some tools that make flight planning a lot easier. One of them is Airmap — a mobile app that allows users to see a detailed map of controlled airspace in their area and submit flight plans for FAA approval. And thanks to a slick new automated approval system rolled out by the FAA earlier this year — and accessible via Airmap — pilots can receive near instantaneous approval (or rejection) for requests to fly in controlled airspace (under certain altitudes). This process used to take weeks or even months, so having access to this system through a simple mobile app makes life a lot easier. Other apps like UAV Forecast and B4UFly also help take the guesswork out of planning a safe, legal and successful drone flight.

Becoming an Aerial Photographer, from the Ground

I took our drone for its inaugural flight in late July. My first goal was to capture photos and videos at past project sites like Edison High School, LaBelle Pond, the Columbia Heights Library, and Hall’s Island. Next, I set about capturing “before” shots of future projects — landscapes that are set to change dramatically as the MWMO and our partners build new green infrastructure around the watershed.

Towerside was a fun area to fly, full of dramatic skylines and decaying buildings that are soon to be redeveloped. I also took photo and video at the future Upper Harbor Terminal and East Side Storage and Maintenance Facility sites. To ensure that I can return to these sites and get shots from the same angles during and after construction, I sometimes use a third-party application called Litchi that lets me pre-program flight routes and then fly the drone automatically while keep the camera focused on specific points of interest. (The routes are saved, so I can come back later and shoot new footage from the exact same angles.)

We also found a couple of innovative uses for our drone that we hadn’t originally envisioned. In November, we took it to Riverfront Regional Park in Fridley and used it to survey the park’s 7,000 linear feet of Mississippi River shoreline. Flying low and slow just above the water, we captured 4K ultra high-definition video of the riverbank, allowing us to spot downed trees and eroding soil. Ordinarily, this type of work would be carried out from the water, but there was too much ice on the river to take the boat out, so the drone allowed us to carry out a task that would have otherwise been impossible.

Using the drone has required me to become familiar not only with the rules and regulations around flight, but also the ins and outs of aerial photography. Since we started using the drone, I’ve spent a good amount of time figuring out how to tinker with the resolution, shutter speed, framerate, ISO, white balance, color profile other settings to capture photos and videos that will meet our needs. (YouTube is a veritable treasure trove of information on these topics.)

From the beginning, one of my intentions has been to use the drone to help create engaging social media content. We’ve published a handful of our best photos on Flickr, and also on our Twitter and Facebook accounts. The response has been extremely positive. One video, showing fall colors along the Mississippi River, reached nearly 60,000 people on Facebook. We also used the drone to document the maiden voyage of our Urban Boatbuilders canoe, and capture some fun footage with our Mississippi River Green Team.

With the arrival of winter, our drone operations will likely be on a hiatus. The manufacturer recommends against flying the drone in below-freezing temperatures, and our next round of construction projects won’t kick off until next spring. I personally am excited to capture a full season of construction from start to finish using the drone. With all the interest that our drone photos and videos have generated on social media, I’m also hoping that we’ll be able to engage residents in new ways that help them appreciate the watershed — along with the work done by our staff and partners to protect it.

In the meantime, enjoy these highlights from our favorite drone footage so far: