News / June 18, 2018

Exploring the High-Tech Stormwater Reuse System at Westminster Presbyterian Church

Downtown Minneapolis can be a challenging place to build green infrastructure. Real estate is expensive, space is tight, and not every landowner is willing to push the envelope on environmentally friendly design. It takes a special kind of motivation to want to build green amid a sprawling jungle of asphalt and concrete.

Westminster Presbyterian Church had that motivation. When it came time for the century-old church to expand and reimagine its spaces for the next 100 years, church leaders went all-in on sustainability. In January, after six years of planning and building, Westminster opened the doors to its new $48 million, 49,000-square-foot addition along the Nicollet Mall. It is a case study in environmental leadership.

Church leaders sought to achieve a litany of environmental goals, and with architecture firm James Dayton Design at the helm, they accomplished many. Highlights include a high-performance building envelope design, high-efficiency heating, cooling, plumbing and electrical systems, locally sourced building materials, and state-of-the-art systems that capture, clean and reuse stormwater runoff.

“The overarching goal was to create an example of responsible urban development,” said lead architect Rob Hunter. “Included in that is stewardship of natural resources and water resources, which was important to the church.”

Stormwater features at Westminster include a 10,000 square-foot green roof, more than 11,000 square feet of native landscape plantings, and a permeable-paver plaza with a snowmelt system. But the star of the show is the church’s high-tech rainwater harvesting and reuse system. Believed to be a first of its kind in the city, the system captures runoff from the church’s roof, stores it in tanks in the parking garage, and then uses it to flush toilets and urinals inside the building, as well as supply irrigation systems and a fountain on the new church plaza.

Mitchell Cookas, a landscape designer and vice president at Solution Blue, oversaw the engineering for the system. Cookas and his company were in a unique position to build such a system, having helped pioneer the use of stormwater in internal plumbing at CHS Field in St. Paul.

“We got to be the guinea pig,” Cookas said of the CHS Field project. “We learned a great deal on that project.”

Using stormwater for internal plumbing was not permitted by code in Minnesota while Westminster was in the planning phase, but the project team heard rumblings that the plumbing code was about to change. Church leaders were committed to innovating, so the team pressed ahead with the design. In the end, the regulations changed just in time for the project team to incorporate the rainwater reuse system into the final plans.

Cookas suggested the team apply for a grant from the MWMO. Seeing a rare opportunity to build an innovative, sustainable stormwater feature downtown, we awarded $600,000 for the project through our brand new Capital Project Grants program. (Westminster became the first project funded through the program, which was under development at the time.) The Metropolitan Council partnered with the MWMO on the project, providing an additional $100,000 stormwater grant to help fund the reuse system.

“At the heart of our Presbyterian tradition is respect for and defense of creation. This project allows us to put our commitment to stewardship of the earth into action, thanks to the support of MWMO, the Met Council and a terrific team of architects and engineers.”

—Rev. Dr. Timothy Hart-Andersen, Senior Pastor

Innovation in Plain Sight

Westminster’s reuse system starts on the rooftop. While the green roof filters stormwater on the addition, the reuse system actually collects the runoff from the roof of the old church building. The water drains to a group of six interconnected storage tanks located in the new underground parking garage. Together, the tanks can hold up to 24,000 gallons of captured stormwater runoff.

Cookas said the garage had to be designed around the stormwater tanks to some extent, in order to accommodate the extra weight, and to have a plan for what would happen if the tanks became damaged or ruptured.

“There are structural considerations to building a system like this,” Cookas said. “In this case, it worked out quite well because there was an underutilized space to locate the tanks.”

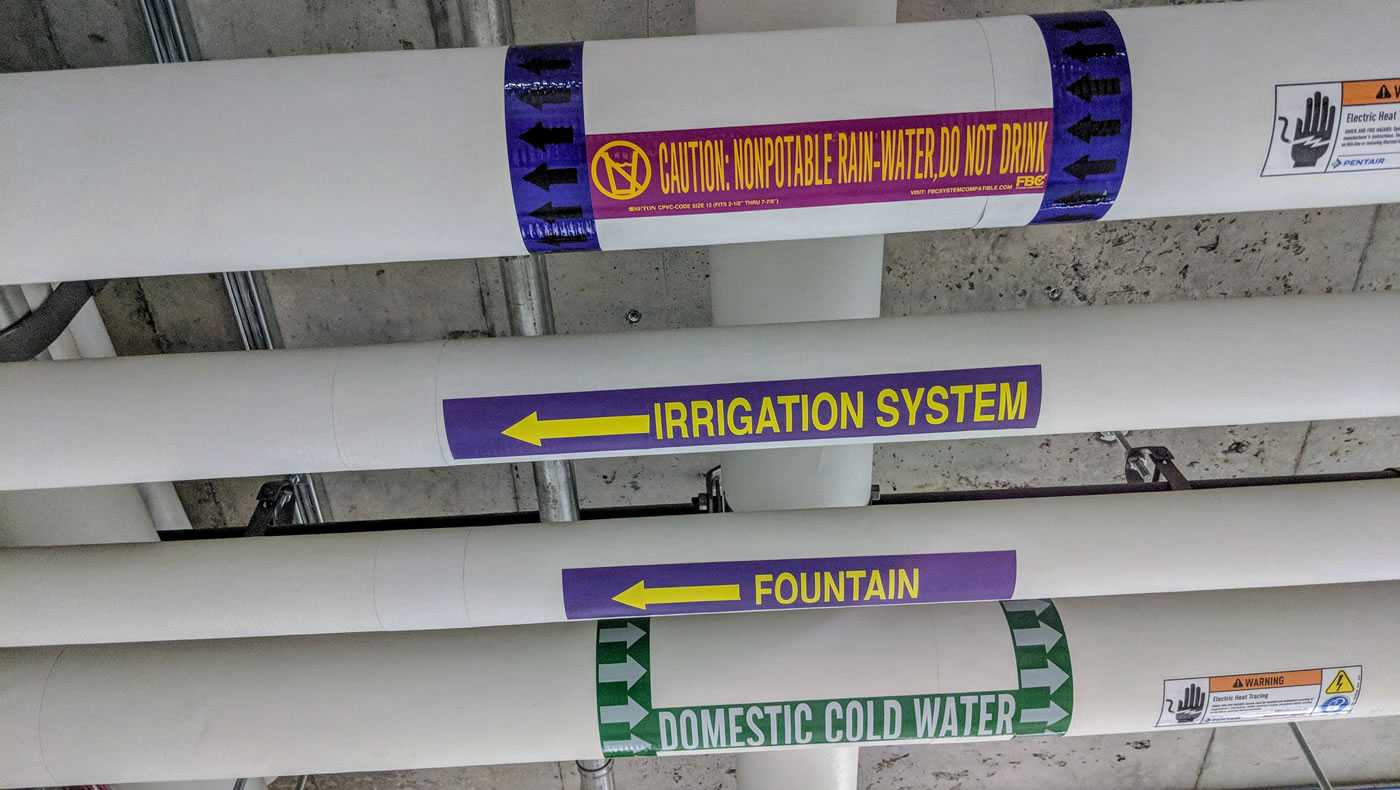

From the tanks, the stormwater is piped into the building’s restrooms, where it’s used to flush toilets and urinals. This is not a simple process. In order to meet building code requirements, the water has to be treated for contaminants first. A UV filter system kills any bacteria in the water before it is pumped to the restrooms. The system also injects blue dye into the water — a precaution that provides a visual indicator to let visitors know the water is not potable.

To run this complex network of pipes, pumps, valves and treatment systems, an electronic water treatment control system runs 24 hours a day. The entire system — pumps, controllers and filters — were designed specifically for Westminster based on the size of the tanks, pipes, etc. The control panel features a graphic user interface that provides maintenance staff with a snapshot of how the system is functioning.

If it seems like a lot of extra work to design and build such a system, Hunter said the benefits outweigh the cost.

“People often perceive new ideas or unique design as a risk, and we don’t view it like that,” Hunter said. “Everyone thinks sustainable development costs more, but from an operations standpoint, it’s most cost-efficient in the long run and it is the responsible way to build.”

Notably, the entire system — tanks, pipes and control panel — is clearly labeled and visible to visitors in the lower deck of the parking ramp. Westminster wanted to put the building’s sustainability features front and center to the visiting public, as a reflection of its values. Westminster and MWMO are currently planning additional educational outreach opportunities surrounding the system to be launched this summer. These include adding interpretive signage, digital displays providing live-updates on water reused by the system and other data, and education programming.

A separate set of pipes carries a portion of the stormwater from the storage tanks to a large, decorative fountain on the church’s new plaza located prominently along Nicollet Avenue. Around the fountain, permeable pavers, native plants and trees add aesthetic charm while providing additional stormwater management.

“Among the principal goals of the church was to be a good neighbor,” Hunter said. “Part of that was to create welcoming and usable outdoor space in an urban environment.”

Communication, Collaboration Keys to Success

The technical challenges behind engineering such a system can be significant, and overcoming them requires a deliberate multidisciplinary approach. Hunter said the key to making it all work is bringing the right people to the table as early as possible.

“I can tell pretty quickly when people know what they’re doing or not, and everyone on this project knew what they were doing. This team had outstanding expertise” Hunter said.

In Westminster’s case, the right people to have at the table included Solution Blue and AKF Group, who served as the mechanical-electrical-plumbing (MEP) engineer for the project, as well as manufacturers and suppliers like Water Control Corporation, who built the treatment system.

“We sat everyone down at the table to make sure that everyone understood the project, challenges and opportunities at hand,” Cookas said.

Team members demonstrated their commitment by going above and beyond, doing pro bono work behind the scenes with the city as the plumbing code was being amended. But ultimately, communication and collaboration were the keys to success.

“Rob is a master coordinator,” Cookas said of Hunter, who simultaneously managed the various needs of the stormwater team and all the other building design teams — not to mention 22 church committees, two boards of directors and 24 separate design consultants.

Hunter, however, said the credit belongs to the church itself. He described Westminster as a “deeply involved urban partner” that sees environmental stewardship as part of their mission. Church leaders see the sustainability features of the building as an extension of their commitment to environmental justice.

“It was the church’s vision to do what they did,” Hunter said. “This was a major project for an organization like Westminster to take on, with a significant capital campaign and a huge building effort. It takes a lot of optimism to do a project like this.”

Learn More

- Westminster Opens Gleaming Expansion to Downtown Minneapolis (Star Tribune)

- Westminster to Open Addition on Nicollet Mall (The Journal)

- Westminster Opens Doors to Historic Downtown Minneapolis Building (Presbyterian Outlook)

- Minneapolis Church Opens New Wing (Presbyterian Mission)