News / June 28, 2016

At the New Columbia Heights Library, a Stormwater BMP Showcase

Managing stormwater runoff used to be a rather unimaginative affair. You dug a hole in the ground, graded the land around it and — presto! — you had a stormwater pond. Little niceties like treating the stormwater to filter out pollutants and protect the local watershed were a secondary consideration (if they were considered at all).

The new Columbia Heights Library shows that civic thinking about stormwater management has evolved quite a bit. The library, which held its grand opening last Saturday, includes a series of landscape features that capture and treat stormwater runoff. This treatment train of stormwater best management practices (BMPs) will keep pollutants out of the local stormsewers and ultimately protect water quality in the Mississippi River and nearby waterbodies.

The MWMO funded the library’s stormwater features, but the idea (and the credit) belongs to the library’s planning committee and the city, which sought to transform what was essentially a giant parking lot along Central Avenue into a showcase of green infrastructure.

To be sure, the estimated 1,800 visitors who attended the grand opening were there primarily to celebrate the new library itself — a long-awaited facility with overwhelming voter support. But the integration of so many visible stormwater BMPs into the library site provides some important educational opportunities. Interpretive signs installed near the various BMPs explain how each one works, and the library plans to integrate the BMPs into a pre-kindergarten educational curriculum focusing on water quality.

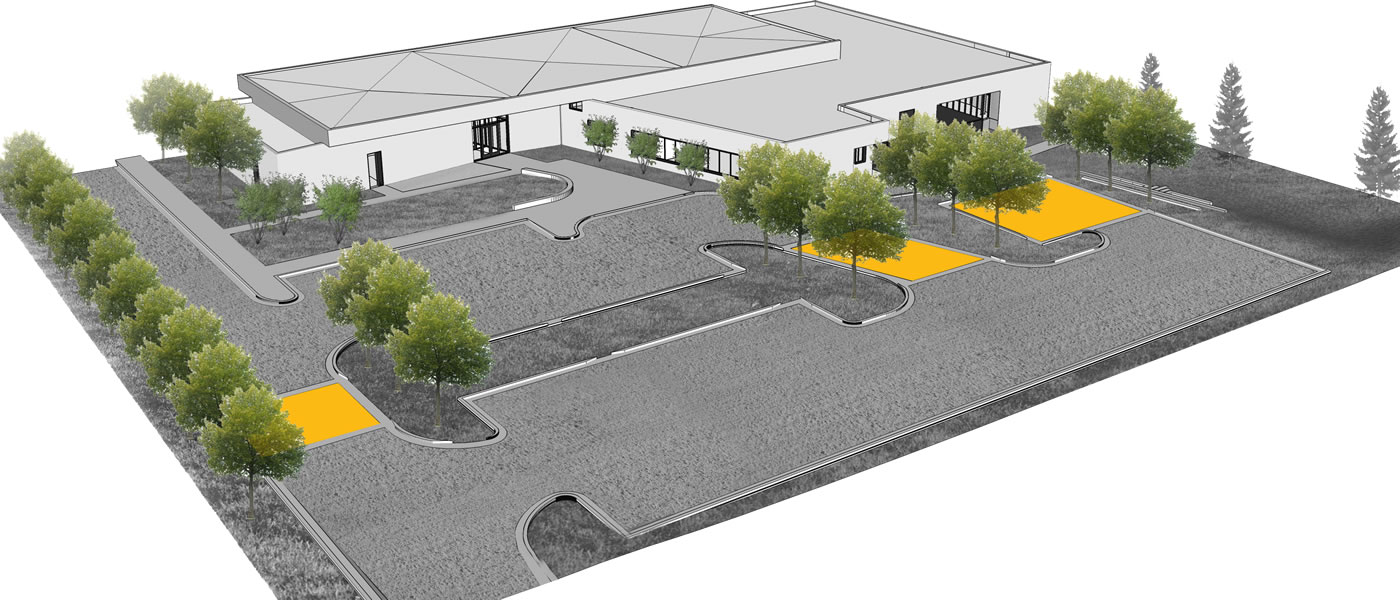

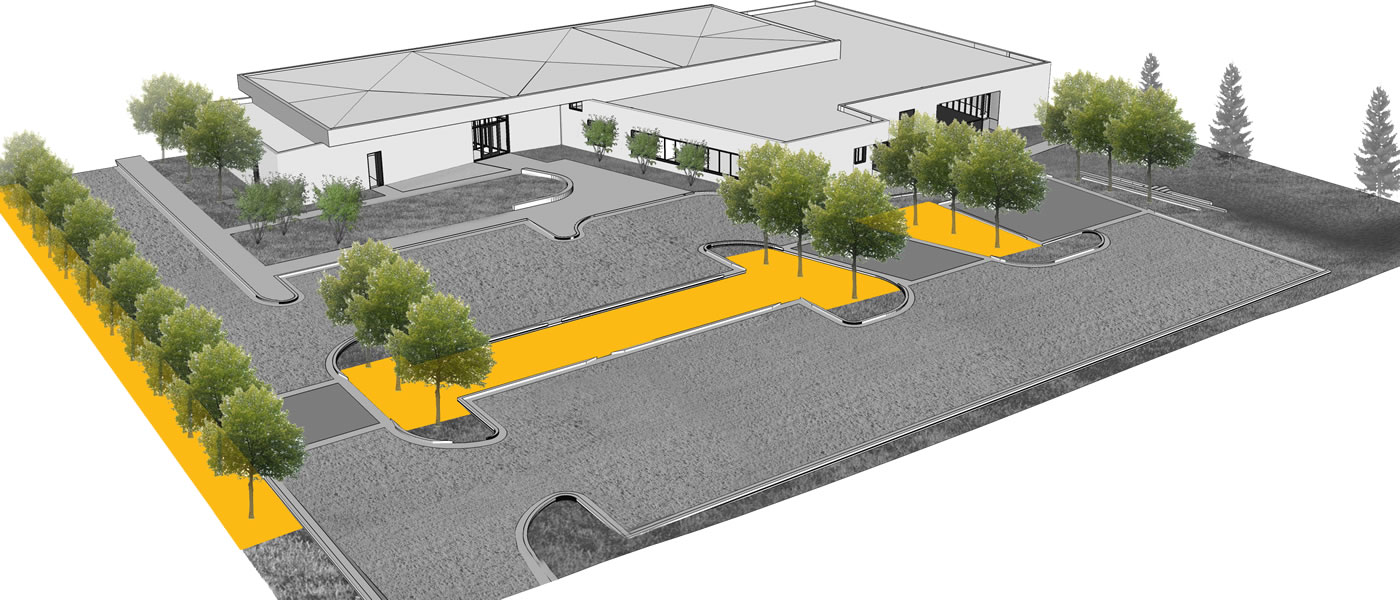

Here’s a look at where the library’s stormwater BMPs are located, and how each one works:

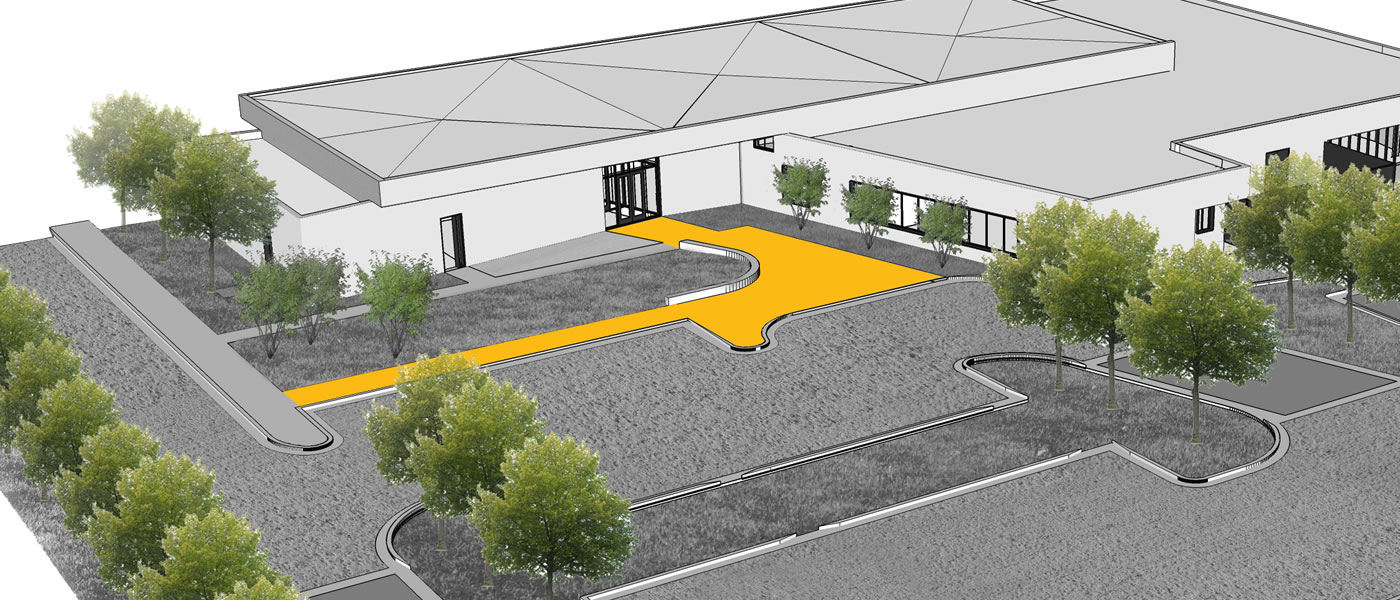

Pretreatment Areas

Runoff from the library roof is directed through a downspout onto grass or crushed stone areas to help stormwater soak into the ground and to remove pollutants.

Permeable Pavements

Three sections of permeable pavement bisect the library’s parking lot. Stormwater runoff drains through gaps between the pavers and into layers of stone and sand beneath. These layers help filter pollutants out of the stormwater. A drainpipe beneath the stone allows excess runoff to move further down the treatment train.

Biofiltration Basins

Three biofiltration basins filled with trees and plants allow parking lot runoff to soak into the soil. The vegetation and soils work together to filter pollutants out of the stormwater before it moves via drain pipe to the next stop in the treatment train.

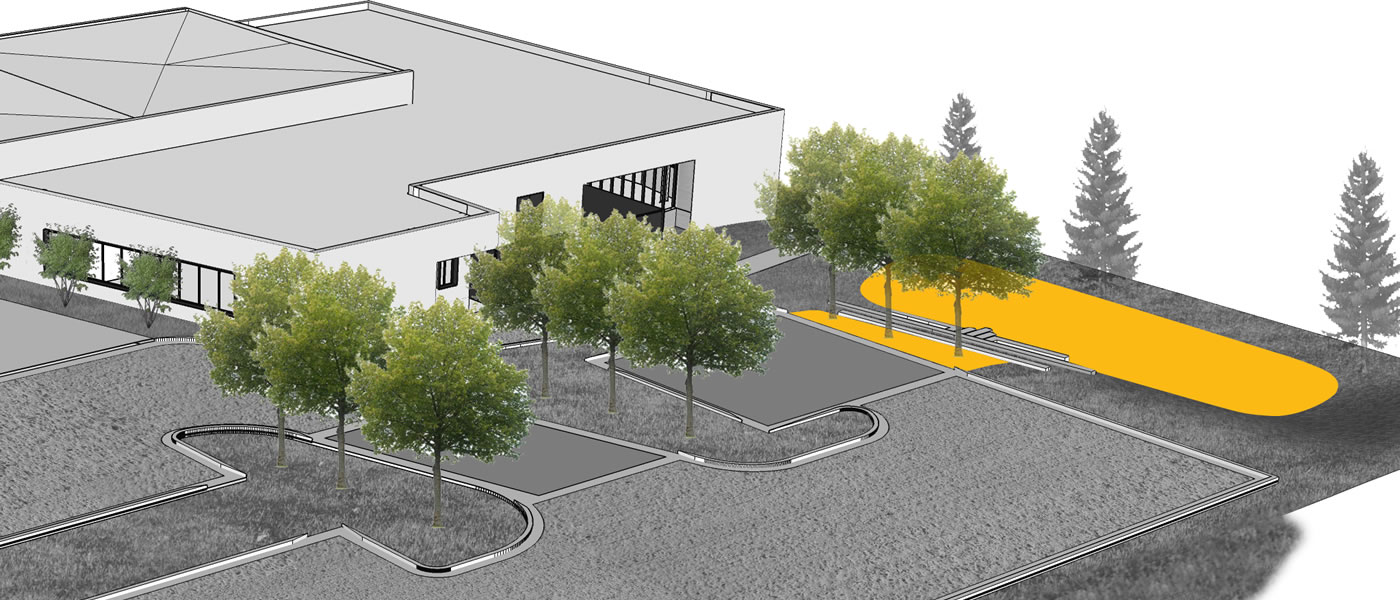

Grit Chamber and Iron-Enhanced Sand Filter

Grit chambers trap heavy sediment and debris by separating them out from incoming stormwater runoff. A grit chamber buried underground next to the library parking lot (beneath the three trees in the illustration) takes stormwater that passes through the permeable pavers and biofiltration basins and cleans it before sending it into the iron-enhanced sand filter.

At the very end of the library’s parking lot is a basin filled with sand that has been enhanced with iron filings. This iron-enhanced sand removes phosphorus — a nutrient and a key source of pollution in waterbodies — from the stormwater runoff before it finally passes through an underdrain and moves into the city’s storm drain system.

Snowmelt System

In the winter, the library’s sidewalk will be free of ice and snow thanks to a snowmelt system buried beneath the concrete. An antifreeze mixture is pumped through tubing beneath the sidewalk, melting the ice without the need for salt or chemical deicers. Road salt and deicing chemicals enter storm drains and discharge into waterbodies, where they become a permanent, impossible-to-remove source of pollution.