News / June 29, 2017

How a teacher used a rain garden to promote hands-on learning

Few teachers would tolerate students standing on their desks and shouting, much less encourage it. But for science teacher Yosefa Carriger, nothing is off the table if it will help her children learn.

Carriger’s seventh and eighth-grade students at Northeast Middle School start each class with a ritual. As they arrive, Carriger picks up a bongo drum and begins tapping out a beat to drown their conversations. On cue, they climb on their desks and bellow out a 10-line creed that begins:

I am in charge of my education! Of my life! I make and live by my choices!

It’s a raucous affair — one that often catches visitors off guard. But it works. The students are energized.

“Even the kids who complain about it — by the time we’re done, it changes the atmosphere in the room,” she said.

Carriger believes passionately in student engagement. She believes traditional teaching methods often leave students behind. And she’s quietly been piloting an experiment to bring a unique kind of hands-on learning into her own classroom with the help of the school’s new rain garden.

Last year, a group of parents in the Audubon Neighborhood Association approached Carriger with an idea. The neighborhood hoped to work with the school to tear out a portion of its underused parking lot and replace it with a rain garden. They wanted Carriger to find a way to bring the project into her classroom as a learning opportunity for the students.

Carriger happily signed on. She saw it as a chance to expose her kids, some of whom don’t get to spend a lot of time in natural settings, to a real-world science project combining science and the outdoors.

“We know hands-on learning is how our brains learn best, using multiple senses and multiple modalities,” Carriger said. “We can talk and talk and talk, but when we show it, it’s so powerful, so impactful.”

Student engagement

The MWMO awarded a pair of Stewardship Fund grants for the project, starting with a Planning Grant to fund the design and engineering work. During this planning phase, Carriger agreed to work with the project engineers and designers from Civil Site Group to involve students in the design process.

A group of 10 seventh-graders signed up to come in after school and work with the engineers to help design the new rain garden. The team from Civil Site Group walked the students through the design process. The engineers explained how rain gardens protect water quality (and why that’s important). Then they showed the students the tools and techniques of engineering and let them bring their own design ideas to the table.

“The engineers were amazing. They printed out everything, all the specs. They treated the children as if they were grown — like they were a part of this design process,” Carriger said.

Feeling empowered, the students sunk their teeth into the project. They studied the rain garden’s design. They watched the engineers take soil borings and even concocted a test where they poured water through different media such as sand and clay to see how it passed through each.

Carriger said the students even advocated for more aggressive stormwater control measures than what the plans called for. The kids’ enthusiasm delighted their teacher.

They’re like, ‘But Ms. Carriger, you know there’s still going to be runoff! This is wrong, you’re not supposed to do it like that!’”

Culturally relevant learning

The students’ enthusiasm for the rain garden project does not come as a surprise to Northeast Middle School Principal Vernon Rowe, who — like Carriger — believes that hands-on learning engages students’ minds in a way that classroom learning does not.

Rowe said traditional approaches to education have helped perpetuate a cultural and racial divide in schools. He thinks one way to break this cycle is to expose kids to situations to which they would otherwise not get to experience — like exposing urban kids to the natural world.

“When you start giving kids more opportunities to learn in different ways, what you’ve done to the curriculum and what you’ve done to the learning is that you’ve made it more relevant and real,” Rowe said.

Carriger said Rowe has an “open-door/open-opportunity” policy that encourages teachers to bring forward new ideas. She credits Rowe’s support and open-mindedness as being key to the project’s success.

For Northeast Middle School, Rowe sees the work that Carriger’s students did with the rain garden as only the beginning. He would like to see the pilot project expanded and imitated elsewhere. He believes these types of learning experiences can be more “culturally relevant” than classroom learning.

“This is just the start to something that could be even greater, if we just open our minds and really think about what is in the best interests of our kids in terms of how they can really learn and grow from this opportunity,” Rowe said.

Two green campuses

An MWMO Action Grant funded construction of Northeast Middle School’s rain garden in 2016. Afterward, the project partners enlisted Carriger’s help again — this time, to involve students in the design of future interpretive signage to be installed at the site.

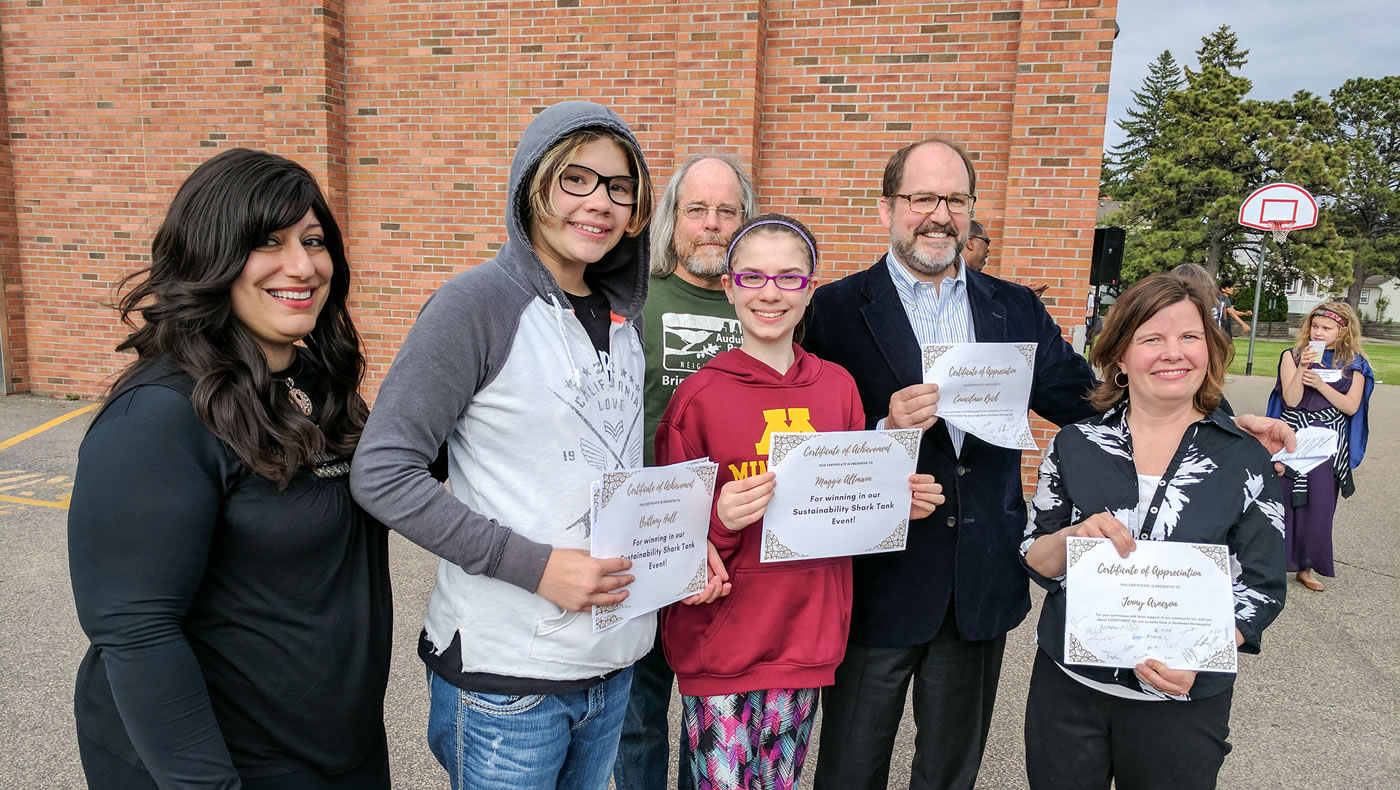

Designers from Wetland Habitat Restorations (now Landbridge Ecological) visited a group of Carriger’s seventh-grade students this spring to gather input on how the signs should look. In addition to providing feedback to the designers, students designed their own versions of the signs, which were displayed at a recent grand opening celebration. The final signage is expected to be installed later this year.

Northeast Middle School is actually the second public school in the area to be re-envisioned as a “Green Campus.” Just a few miles away, Thomas Edison High School has also been upgraded with a series of green features, including a stormwater reuse system, a rain garden, a permeable paver parking lot and a tree trench. An MWMO grant helped pay for the upgrades, and — as with Northeast Middle School — designers from Wetland Habitat Restorations worked with the students at Edison to help create interpretive signage.

MWMO Board Chair Kevin Reich, who represents the area on the Minneapolis City Council, said the two campuses are connected, as many Northeast Middle School students go on to attend high school at Edison.

“This is really the next generation of sustainably landscaped school campuses inspired by Edison,” Reich said. “Both campuses will help to protect our water quality, create new educational opportunities for students and serve as amenities for the entire community.”

Northeast Middle School plans to continue using the rain garden for teaching purposes, as it fits in nicely with the school’s science curriculum. MWMO Youth and Community Outreach Specialist Michaela Neu has been assisting Carriger throughout the process as she brings the rain garden project into the classroom.

In the meantime, Carriger plans to keep up the energy in her classroom. She said it’s her students’ energy that keeps her going.

“They keep me still growing and still hoping and still trying to look at the world through their eyes,” Carriger said.